Lisbon is having a moment. Featured everywhere from travel publications to television programs, Europe’s second-oldest capital (after Athens) is being hailed as an under-the-radar, affordable destination. It has also become easier to get to thanks to TAP Air Portugal’s recent expansion of its North American gateways.

And why not. The capital of Portugal and one-time home of world-class explorers Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and Prince Henry the Navigator has it all. Centuries of history. Check. Mild climate. Check. Interesting architecture. Check. Loads of culture. Check. Museums and monuments. Check, check. Food, wine, and nightlife. Check, check, and check. Nearby towns with plenty to see and do, as well as the rest of the country just waiting to be explored. Check and check.

But ask if Lisbon is wheelchair accessible, and the answer is less rosy. You’re likely to hear that the city is built on seven hills like Rome (actually, it’s six), which means a lot of ups and downs if you’re walking or rolling. What you may not hear is that most of the sidewalks not only are irregular, they’re made of polished limestone and brick tiles, resulting in bumpy going for wheelchair riders and slippery surfaces for pushers. Unexpected steps in the middle of sidewalks are not uncommon. Curb cuts? Don’t count on them.

Still, the situation isn’t all that bad. I spent more than a week in Lisbon this summer and didn’t feel deprived—at least not much. However, I always travel with a friend who pushes my “companion” chair (it has small wheels; I can’t use my arms), so he was able to deal with issues a solo wheelchair traveler might find impossible.

In general, the most accessible neighborhoods are Baixa and Cais do Sodré, the downtown; Belém, departure point for the explorers and a major tourist attraction, and Parque das Nações (Park of Nations), an area of new high rises on the east side of town. More interested in the old than the new, we ignored the last, though it’s probably the most accessible with attractions such as the Oceanarium and cable car.

We also found that more museums were accessible than churches, several parks were perfect for hanging out, and a couple of the famed look-out points were reachable with a bit of planning.

Restaurants turned out to be a mixed bag but admittedly weren’t chosen specifically for accessibility, though other people have noted that outdoor cafes tend to be good bets. This mini guide doesn’t address hotels because we stayed at a lovely Airbnb—called Jewel’s Apartment—that was accessible enough for me (one small step at the building entrance; walk-in shower), and our host, Pedro, was wonderful.

GETTING AROUND

The most important thing to know about Lisbon Airport, which is about 4.5 miles north of the city’s center, is that there are relatively few jetways, so many planes park remotely and bus passengers to and from the two terminals. MyWay provides services for people with disabilities, and you should book the help you need with your airline or travel agent or up to 48 hours before your flight’s published departure time. At the airport, contact MyWay at the Designated Point of Arrival, a telephone booth marked with its logo.

My experience with MyWay was relatively good. Upon arriving from Chicago, we had to wait for everyone else to deplane before a vehicle with a lift up to the plane door came to fetch us and take us to another vehicle (a van with a lift) that took us to the terminal, where we were met by a MyWay employee who whisked us through all the usual rigamarole without any lines. Departing, MyWay took us from check-in, through security (again, no lines), and up to the TAP business lounge, then came in a timely fashion to take us through passport control (no lines), to the gate and, when it was time, onto the plane, which did have a jetway.

While there seemed to be no problem bringing the wheelchair to the gate, mine is small enough to fold up and fit in an overhead bin, so I wanted to stow it in the cabin. Even though I had prearranged with TAP Air Portugal to do this, I got a lot of push back from gate personnel despite citing ACAA provisions requiring carriers to allow assistive devices that fit under the seat or in an overhead. I prevailed but only when my friend folded the chair up and demonstrated that it fit—to the surprise of the airline staff.

Public transportation isn’t reliably accessible even when it’s billed as such. We took the 735, the supposedly accessible bus near where we were staying, several times with varying results: One time the fold-out ramp was missing the handle to open it; another time the ramp was fused shut, and one time it worked. The bus was almost always crowded, making it hard to wedge the wheelchair into the designated space. On no occasion did the driver offer any assistance. Unfortunately, the trams—including the famous Tram 28–are totally inaccessible, as are the funiculars.

Trains didn’t fare much better. At the Alameda Station, we were greeted by an employee who informed us that two elevators (of five total) were broken, but thankfully, the one we wanted was working. On the plus side, she escorted us all the way to the train and called ahead to a colleague to meet us at our destination, but he just said “hi” and left us on our own to find the three elevators necessary to exit.

The sole elevator at the Rossio Station, which serves the fairytale town of Sintra, was broken the day we needed it, and we had to go to the back of the building and up switchback ramps to get to the ticket office and trains. A couple of train compartments were marked with wheelchair symbols and had ramps requiring staff assistance, but no one was around, so my friend lifted me on board in my wheelchair with the aid of other passengers. The same thing happened returning from Sintra, and the crowded trains had no designated spots for wheelchairs.

Mostly, we used Uber, which is inexpensive. The drivers tended to be helpful and had no problem folding up the wheelchair and putting it in the trunk. On the other hand, their GPS systems sometimes took them to inaccessible entrances to museums and such, and they didn’t know where to go to let us off.

Having a wheelchair often enabled us to bypass long lines and pay reduced entrance fees, though fewer things were free than in other countries. I’d recommend buying the Lisboa Card for free or reduced admissions and shorter lines, even if you can’t make full use of the free public transportation.

DOWNTOWN (Baixa and Cais do Sodré)

Praça do Comércio (Comercio Square), also known as Terreiro do Paço or “the palace’s square” for the royal palace that stood here for more than two centuries until the Great Earthquake of 1755, quickly became our point of reference for downtown. Adjacent to the Tagus River, the vast square with an equestrian statue of King José I in the center is completely accessible, as are the outdoor cafes and restaurants on its three neoclassical arcaded sides (though their washrooms may not be). The triumphal arch on the north side leads to Rua Augusta, the main pedestrian shopping street, with more cafes set up in the center and frequent street performers.

While there are two tourist info centers on the square, the main Turismo de Lisboa office and shop are around the corner on Rua do Arsenal. Besides loads of information, the office has a very nice accessible washroom.

Back on the square, the completely ramped Lisboa Story Centre offers an hour-long interactive tour of the city’s history that’s geared to school kids but isn’t a bad way to pick up a little background. The centerpiece is a re-enactment of the 1755 earthquake on three big screens with plenty of scary sound effects.

After looking at several menus one evening as the sun was starting to go down, we settled on Can the Can, partly because we were able to get an outdoor table right in front. The name plays on the concept of using Portuguese conservas (canned fish), and prices are reasonable given the location. We enjoyed a trio of pataniscas, crispy irregularly shaped cod fritters with slightly creamy salt cod interiors; tender octopus salad with purple onion and tomato in a light olive oil dressing, and “anchovied” sea bass, two crisp-skinned fish fillets with Yukon gold potatoes in an olive oil sauce flavored by anchovies. Both the rosé and red wine specials went well with the food, and service was leisurely but extremely nice. Our waitress even told me that, since their washrooms weren’t accessible, she’d be happy to give me a euro to use the public one.

Downtown’s other more-or-less accessible squares and streets range from Praça do Município (Municipal Square), where you’ll find City Hall and the newish Money Museum (in a former church), to Avenida da Liberdade, the wide Champs-Elysees-style designer-shop-lined boulevard that runs for a mile from Restauradores Square to Marquês de Pombal Square.

One of the best-loved attractions is the Santa Justa Elevator, a filigreed cast-iron tower designed by the Portugal-born French architect Raoul de Mesnier du Ponsard, an apprentice of Gustave Eiffel, which explains its similarities to Paris’ Eiffel Tower. Built in 1902, the 147-foot-tall Neo-Gothic construction connects downtown to Bairro Alto, the highest point of the city. You can bypass the steps to the elevator by going into the building, but you’ll only be able to get to the mid level—which has great views over tile roofs—because a spiral staircase goes to the top. You’ll also need a Lisboa Card or cash; credit cards aren’t accepted.

A 10-minute walk along the riverfront from Comercio Square leads to the domed TimeOut Ribeira Market (mercado.ribeiro@cm-lisboa.pt), the flagship food hall of the namesake publication with restaurants and other vendors curated by its writers and editors. Here you’ll find stands from chefs Alexandre Silva, Marlene Vieira, Henrique Sá Pessoa and Vítor Claro, as well as a shop selling conservas, a chocolatier, and a wine store. Communal tables fill the hall’s center, but all of them are high except for those on either end. We savored picture perfect tuna tartare from Tartar-Ia but were disappointed by Monte Mar’s small garlic shrimp in a salty sauce. Best were the eggy chocolate sponge cake from Nós É Mas Bolos and the famous pastéis de nata from a branch of Manteigaria, which frequently wins awards for its signature flaky, crunchy custard tarts. A dwindling section of the old traditional produce-meat market remains, but it looked sad on our visit. There is an accessible washroom.

BELÉM

There’s so much to see in this neighborhood, it’s hard to know where to start. So I’ll begin with three iconic monuments you can skip going into, because they’re best viewed from the outside.

The 25 de Abril Bridge, completed in 1966 and named for the dictator Salazar until after the revolution of April 25, 1974, is a 1.5 mile long (or so) suspension bridge over the Tagus River. It resembles San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, only its central span, the longest in Europe at 3,323 feet, is longer.

Belém Tower, built in 1515 as a fortress to guard the entrance to Lisbon’s harbor, was the starting point for many of the voyages of discovery and has related stonework motifs, sculptures depicting historical figures such as St. Vincent, and a rhinoceros that inspired Dürer’s drawing of the animal. Architect Francisco de Arruda also incorporated Moorish influences, arcaded windows, Venetian-style loggias, and a statue of Our Lady of Safe Homecoming, a symbol of protection for sailors on their voyages. Inside, visitors line up to climb the steps of this UNESCO World Heritage Site, but there’s really no point.

There’s an elevator to go up inside the Discoveries Monument, but this sweeping sculpture of a three-sailed ship built on the north bank of the Tagus River in 1960 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the death of Prince Henry the Navigator is most impressive for the historical figures on the outside. They include King Manuel I carrying an armillary sphere, poet Luis de Camões holding verses from “The Lusiads,” Vasco da Gama, Magellan, Cabral, and several other notable Portuguese explorers, crusaders, monks, cartographers, and cosmographers. Prince Henry himself is at the prow holding a small vessel. The only woman is Queen Felipa of Lancaster, his mother.

On the other hand, do go inside the Jerónimos Monastery, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983 and designed in 1501 by the Portuguese architect Diogo de Boitaca to celebrate Vasco da Gama’s successful voyage to India. Da Gama’s tomb is in the Gothic Church of Santa Maria, along with that of poet Camões, whose “The Lusiads” glorifies him and his compatriots. Other Portuguese notables entombed here include King Manuel and King Sebastião, and poets Fernando Pessoa and Alexandre Herculano.

The maritime motifs of the style that became known as “Manueline” are even easier to see in the magnificent cloisters, where each column is differently carved with coils of rope, sea monsters, coral, and other designs evocative of that time of world exploration at sea. The former refectory off to one side has beautiful reticulated vaulting and tile on the walls depicting the Biblical story of Joseph.

Both the church and the cloisters are ramped, and we were allowed to enter immediately despite the lines. There is an accessible washroom, but it’s small and kept locked, so you have to ask a security guard to open it.

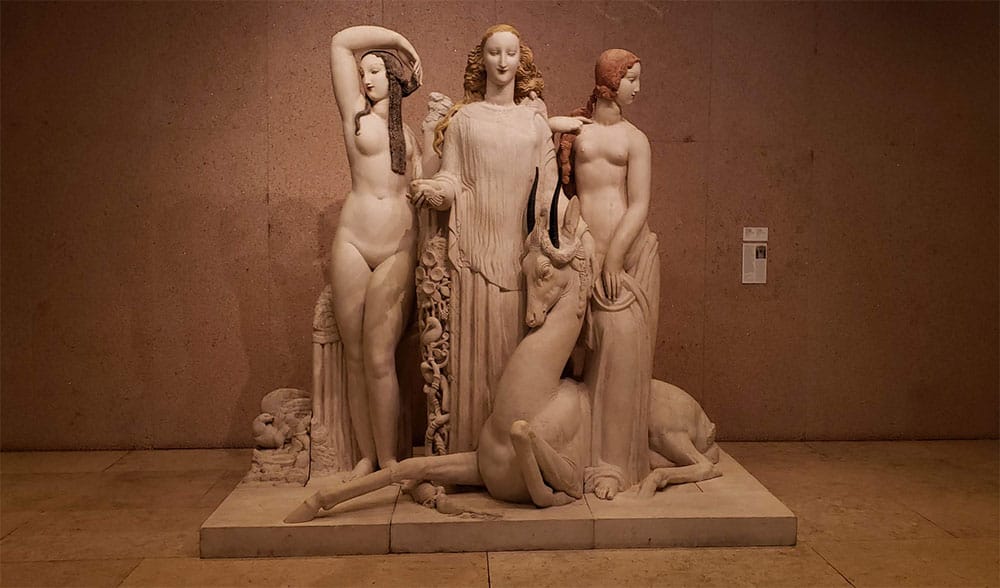

In the west wing of the monastery is the Archaeology Museum, which brings together ancient Egyptian, Greco-Roman, Visigothic, and Moorish artifacts, mosaics, funerary art, and ornaments from excavation sites all over the country. The highlight is an exhibit of early Portuguese jewelry, much of it beautifully wrought gold.

With our Lisboa Cards ready to swipe on a machine that registers their validity, we were able to bypass both the line of other cardholders and that of people waiting to by tickets. The galleries were ramped as needed, and some had replicas of objects for people with limited sight to touch. Captions were in Portuguese, English and, in some cases, French. The accessible washroom was much less crowded than that in the church.

Across the street from the monastery is the Belém Cultural Center built in 1992 to host Portugal’s presidency of the European Union. Numerous international exhibitions have been held here since, and the arts complex has the city’s largest auditorium. The real reason to visit, though, is the Berardo Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, one of the world’s finest privately amassed collections of works by Warhol, Picasso, Dali, Duchamp, Magritte, Miró, Bacon, Jackson Pollock, Jeff Koons, and many others, organized by movement—Surrealism, Constructivism, etc.–with captions in Portuguese and English.

Although the museum, which opened in 2007, is accessible, getting to it from street level requires mastering a self-operated wheelchair stair lift up a flight of about 10 steps. There are accessible washrooms, and a first floor cafe and restaurant with a garden overlooking the river and Discoveries Monument.

Two nearby museums offer a taste of the opulence of 18th-century Lisbon and the wealth of European royal families. The Coaches Museum, accessible once you cross the bouncy black-brick courtyard to the ticket office, has the world’s largest and most valuable collection of impossibly ornate coaches, many of them ceremonial, such as one with gilded figures on the tailgate showing Lisbon crowned by Fame and Abundance. The often-overlooked Ajuda Palace, never completed as planned due to the exile of the royal family in Brazil caused by the French invasion in 1807, is richly adorned with furniture, paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and exceptional decorative arts, albeit a little faded feeling. The public tour includes state rooms, the king and queen’s homier private rooms, and the everyday family dining room, but the wheelchair-accessible route—arranged in advance or by having an able-bodied person go in and ask—goes through many rooms that aren’t open to the public (some undergoing renovation) and includes a ride in a jewel of a wood-paneled elevator with a red-velvet seat.

Judging by the long lines outside (just like all the guidebooks say), everyone goes to the tiled, multi-room Antiga Confeitaria de Belém for the famous pastéis de Belém, the custard tarts the pastry shop has been serving since 1841. The secret recipe, passed down from the monastery, is supposedly different from that for other versions. I found the crunchy crust too buttery, and the custard too sweet, even with the customary sprinkle of cinnamon. You can watch the bakers at work in the glassed-in kitchen near the large accessible washroom (from which I saw four able-bodied women emerge together). Despite the lines, there seemed to be many empty tables inside, so consider enjoying your tarts on the spot rather than getting them—packed six to a cardboard tube—to go.

FIVE MORE ACCESSIBLE MUSEUMS AND ONE MONUMENT

The National Museum of Ancient Art, in a 17th-century former palace, has a terrific collection of Portuguese and European art from the 12th to the 19th centuries. The most important Portuguese painting probably is Nuno Gonçalves’s late 15th-century masterpiece, usually known as the “Panels of St Vincent” (although its subject is disputed), but I was equally thrilled by the Bosch triptych “Temptations of St. Anthony” and works by Raphael, Dürer, Memling, and other masters, as well as religious sculptures with the polychrome amazingly intact. You’ll also find Chinese porcelain, Indian furniture and African carvings. Well laid-out and lit, the museum is accessible (except for the lower level) if you go in the front entrance, and the accessible washroom is at the back of the excellent shop.

The Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, housed in several buildings spread over a beautiful park, showcases one of the world’s finest private art collections, amassed over 40 years by oil magnate Gulbenkian, who adopted Portugal as his home and donated all of his treasures to the country when he died in 1955 at the age of 86. Besides everything from priceless Egyptian artifacts to stunning European paintings by big names, the Founder’s Collection includes fine French furniture and textiles, Persian tapestries, Japanese prints, Chinese porcelain, and breathtaking Turkish ceramics and glass. The pièce de résistance is the Lalique room with whimsical jewelry featuring flora and fauna like the dragonfly pin, as well as a serpent mirror I coveted. The Modern Building has three floors of paintings, works on paper, sculpture, and installations by Portuguese artists and immigrants. Both buildings are accessible (with accessible washrooms), as are the grounds, though the wheelchair signs sometimes mysteriously lead to steps.

The Orient Museum, in a converted warehouse, focuses on the interaction of Portugal and the Far East. Sections, subdivided by country, are devoted to themes such as the Portuguese influence on the Far East and the Portuguese as collectors of Far Eastern art and decorative arts, which often meld East and West. A second-floor exhibit through the end of the year spotlights Chinese opera with more costumes, artifacts, film clips, and information than you can imagine. The museum, which also functions as a cultural center, is fully accessible and has a fifth-floor restaurant offering a 20 euro lunch buffet and great views.

The National Tile Museum, in what once was the Madre de Deus Convent, is a bit out of the way but well worth the trip. The one-of-a-kind collection explains the history of azulejos, decorative ceramic tiles, and how they’re made, as well as showing a splendid array of tiles, tile portraits, and tile murals from the 15th century through the 20th. The chapel dedicated to St. Anthony and chapter house are particularly splendid; the former is up a flight of steps, but you can view it through a window from above. The rest of the museum, which also has exhibits of ceramics, figurines, and dinnerware, is accessible. Don’t miss the 75-foot-long blue-and-white tile mural of Lisbon’s cityscape created in 1738 before the Great Earthquake. It’s on the second floor, as is the accessible washroom.

The Air Museum, outside of Sintra (about 30 minutes from Lisbon), has an extraordinary collection of vintage and replica aircraft and accouterments spotlighting a century of Portuguese aviation. The exhibits are in three fully accessible historic hangars and connected rooms, among them one devoted to pioneers and another to TAP Air Portugal. Don’t miss the Beechcraft Bonanza F-33A , registration CS-AZI. It belonged to António de Sousa Faria e Mello (1942-2006), a pilot who refused to be sidelined by a spinal chord injury that left him in a wheelchair, took a course in the U.S. for paraplegic pilots, and racked up two world tours as well as other feats. His painted portrait is next to the plane, which was adapted for his needs and is emblazoned with “International Wheelchair Aviators.”

The National Pantheon, formerly Santa Engracia Church, is on the site of an earlier church that was torn down after being desecrated by a robbery in 1630. An innocent man was executed for the crime, and legend has it that he cursed the building, which may be why it took until 1966 to complete its reconstruction—based on St. Peter’s in Rome. The domed building, on the plan of a Greek cross with an interior covered in multicolored polished marble, houses the tombs of several Portuguese presidents, quite a few of the country’s literary lights, and two unlikely luminaries: Amália Rodrigues, the most famous fado singer, and Eusébio da Silva Ferreira, one of the greatest footballers (soccer players) of all time. The accessible entrance is at the back of the building (one small step), but there’s no accessible washroom. The “Feira da Ladra,” Lisbon’s flea market, fills the surrounding streets on Tuesdays and Saturdays.

A FAVORITE PARK

The Jardim Guerra Junqueiro, named for a 19th-century poet, journalist, and politician entombed in the National Pantheon and also known as the Jardim da Estrela, is a picture-perfect and completely accessible 19th-century park with winding pathways, lovely plantings, ponds with ducks playing, a cafe, and an old wrought-iron bandstand near the center. We discovered it when we tried to go to the Estrela Basilica across the street, which turned out to be totally inaccessible. Not only that: While the church’s plaza was incredibly windy, the park was an oasis of calm tranquility. We bought some freshly squeezed orange juice from a cart and were happy to just hang out.

A FAVORITE LOOKOUT POINT

Miradouro das Portas do Sol, one of Lisbon’s many viewpoints (miradouros), is a great place to be on a Sunday afternoon. The view out over the red-tile roofs of the Alfama neighborhood to the river is spectacular. There are stalls selling local crafts and touristic knickknacks. And depending on where your relax, you can hear everything from classical to popular music. We listened to a fado singer for a while, then found a fab Afro-Pop group with people dancing on the terrace all around.

Anne Spiselman is a freelance writer specializing in dining, culture and travel.