What is art?

According to Encyclopedia Brittanica, art is “something that is created with imagination and skill and that is beautiful or that expresses important ideas or feelings.” It is presented in many forms: painting, sculpture, music, theater, literature, dance, and multimedia — just to name a few. Speech, verbal or otherwise, is also an expression of ideas or feelings, and thus qualifies as a work of art. Art is, in effect, an expression of our unique and individual experience of humanity, and the creation of art is something of which we are all capable.

A museum connecting disabled artists to the world

During a recent trip to Liège (about an hour east of Brussels, Belgium), I visited the Trink-Hall Museum, host of a contemporary collection of nearly 4,000 artworks created exclusively by disabled artists. The museum’s mission is an ambitious one:

We envisage a revolving door: a museum in full throttle with the ambition, however modest, to change the direction of the world; surmounting the obstacles and contradictions inherent to any museum project; celebrating art without restricting it, collating without diminishing it, empowering without imposing it, which, in these dark days of globalization, champions the singularities and the expressive power of fragile worlds.

Trink-Hall, a revival of the former MADmusée which existed for more than 20 years, tells the story of life’s contradictions through artwork produced by people with intellectual disabilities. The museum’s collection includes works from disabled artists the world over, but there is indeed a special place for Belgium’s very own creators.

Selected works by disabled artists

The museum’s relatively small size permits only a limited number of works to be displayed at any given time. Here, I have shared a few of the pieces that I am told are on longer-term display. No two visits to an art museum will be the same — with each subsequent visit, we bring additional knowledge and new perspectives, which we hope will allow us to draw something more from the delightful well of artistic expression on display.

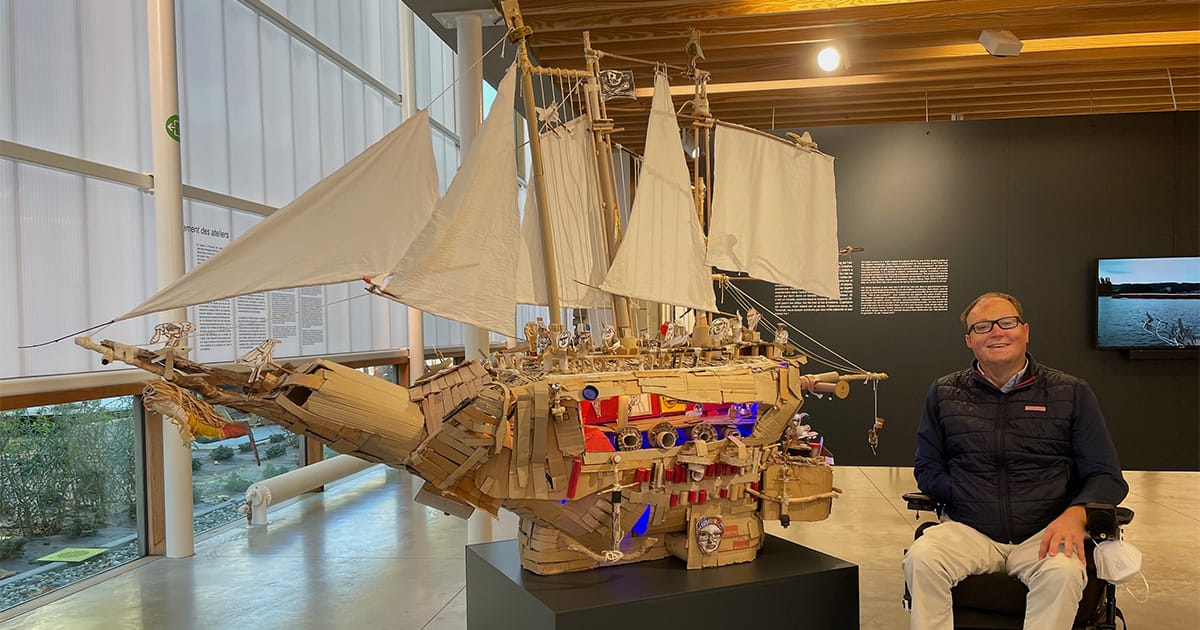

The ideal museum by Alain Meert

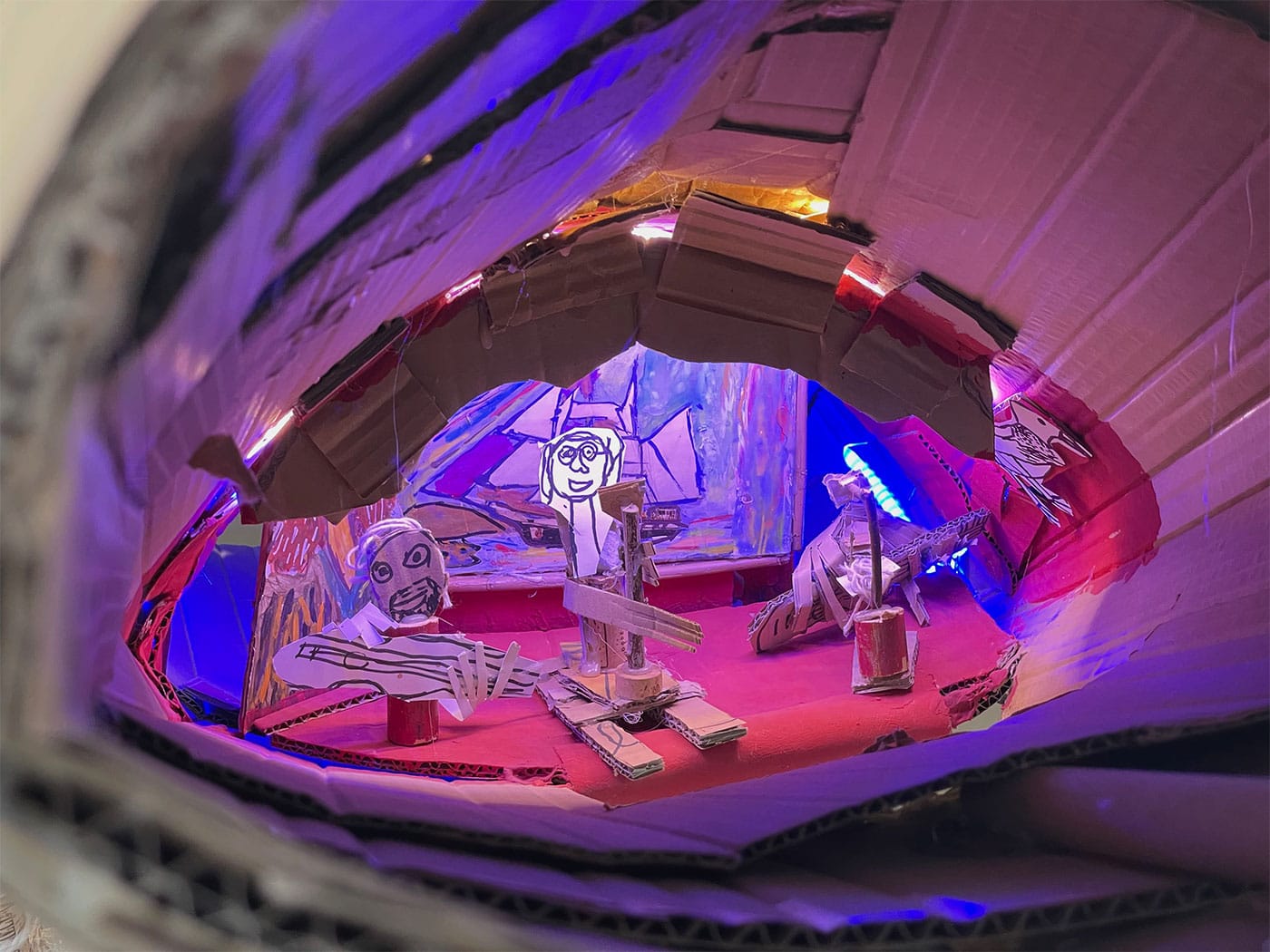

Prior to the opening of the Trink-Hall Museum, a local artist, Alain Meert, was asked to produce a piece to answer the question, “What is a museum?” His response was Le musée idéal (2019), which translates to The ideal museum. The work, a large sailboat constructed with cardboard, presents numerous scenes that provide valuable insight into what is perhaps the larger question — what is art?

The ship greets visitors immediately upon entry to the museum. Its complexity, creativity and the depth of understanding that it reveals spoke to me in a way that few other works of art have done — it contradicts every harmful notion of disability that has entrenched itself in our society’s collective misunderstanding of human potential.

The ship creates a three dimensional world that captures one’s own imagination. It is a museum in its own right; a museum within a museum. It more than answers the original question, and leads us to understand that art is bounded only by the limits of human creativity and expression. Art is painting, performance, sculpture, architecture, engineering and so much more — The ideal museum captures it all, inviting us to dream of limitless creativity and innovation.

If you’d like to learn more about the artist, view his portfolio on the Créahm website.

Various works by Paul Duhem

The late Paul Duhem (1919-1999) first picked up a paintbrush at 70 years old after entering Bruno Gérard’s workshop, La Pommeraie. His painting was ritualistic — for a decade, he painted the same series of motifs, each unique in its own way with variations in color and style.

Trink-Hall boasts a large collection of Duhem’s works, with 18 watercolor paintings shown in a single exhibit. Like many others, I was surprised to learn of the artist’s output: each day, Duhem produced 3 paintings in the morning and 3 in the afternoon… for a full decade! The dedication to his craft is admirable and worthy of celebration.

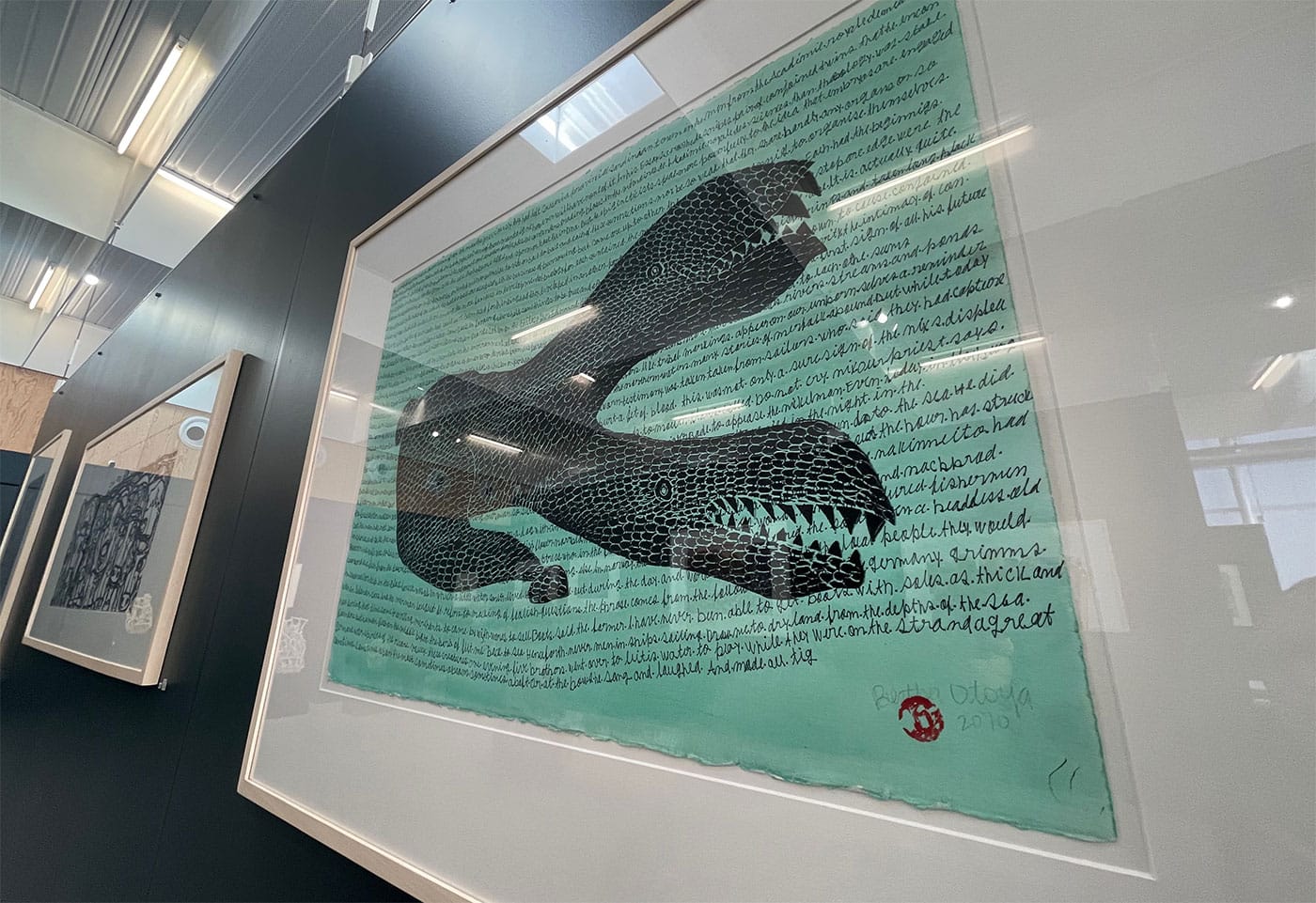

Artwork by Bertha Otoya

Bertha Otoya was born in Peru in 1979 and later moved to the United States, where she started working with Creativity Explored, an organization that describes itself as a “studio-based collective in San Francisco that partners with developmentally disabled artists to celebrate and nurture the creative potential in all of us.”

Creativity Explored describes Bertha’s artistic style in this way:

Otoya often begins on a white ground by painstakingly appropriating, then recopying, writing from a variety of source texts, mostly written in English, not her native language. Through this meticulous repetition of writing, the resulting text becomes a collage of prose that warrants close inspection if the hidden meaning between her chance juxtapositions is to be revealed. Layered over the text is an array of fabulous (and sometimes terrifying) beasts and figures whose solidity and careful rendering add an anchoring counterpoint to the ephemeral, shifting text beneath.

To learn more about Otoya or to purchase her artwork, visit her artist’s page on Creativity Explored.

Various works by Jean-Marie Heyligen

Jean-Marie Heyligen (b. 1961) is a Belgian plural-form artist, who is revered for his artistry in painting and sculpture. A number of his works are on display at the Trink-Hall Museum, including an impressive sculpture that is one of the largest pieces in the collection.

The sculpture’s wooden base serves as a foundation for the application of various materials — keys, coins, chains, nails, and even a wheel. The purposeful assembly of abandoned materials to create a warrior-like figure reminded me of the work of an artist I once met in Selma, Alabama: the world-renowned Charlie ‘Tin Man’ Lucas. It takes a clever mind to repurpose junk and discarded items into meaningful art.

Painting by Michel Petiniot

Michel Petiniot is a local artist who has participated in workshops at Créahm for approximately 30 years.

Many of his works are on display at Trink-Hall, including a popular tapestry, “La Montagne oculée,” which was produced in 2019. My eyes were drawn to the painting pictured above, created in 2012, crafted with acrylic and India ink on paper. The piece depicts the natural world and a civilization in a unique and compelling way. I couldn’t take my eyes off of this work — at first glance, it appears to be somewhat chaotic, but it ultimately evoked a sense and feeling of peace in me.

Practical details: Location, transportation and admission

The Trinkhall Museum is located at the center of the Parc d’Avroy in Liège, just steps away from the intersection of Boulevard d’Avroy and Traverse Botanique. A large number of city bus routes stop nearby, including the following: 1, 25, 27, 30, 48, 64, 65, 90, 94, and 377. The majority of city buses in Liège provide wheelchair access via a ramp at the center door.

Admission to the Trink-Hall is priced according to the following schedule:

- Adults: 7 €

- Seniors (over 65 years): 5 €

- Job seekers – Students – Teachers: 3 €

- Free of charge: Under 12 years

For more information useful in planning your visit, consult the Trinkhall website.

Bonus: Some thoughts on assessing the value of art and what we see

I love to write and oftentimes get carried away with words, exploring tangential thoughts that might distract readers from the point of an article. Typically, I delete them — but in an article celebrating art, I think I’ll leave a few extra thoughts for you to consider.

The value of art (and the success of an artist) is often measured by its popular appeal — the degree to which it elicits a response, admirable or otherwise, from those who discover it… and, ultimately, by the number of people it reaches. That may not be the correct approach.

Museums showcase art that reflects the public’s interest and desire. The Louvre, the world’s most-visited museum, unsurprisingly presents the world’s most popular and easily recognizable painting: Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Like millions of others, I was drawn to Paris, France to see the Mona Lisa, but left thinking that the masterwork might be a tad bit overrated. I am by no means qualified to be an art critic, but the thought that the most popular work of art might not be the most valuable led me to question: How many talented artists have I not yet discovered? Is the luck of an artist in reaching the tipping point of mass appeal really the proper measure of his/her contribution?

The answer to that question is obvious, and it’s precisely why museums like Trinkhall are important — they are places that permit us to discover artists whose unique and individual expressions of their humanity (read: their art) also have merit.