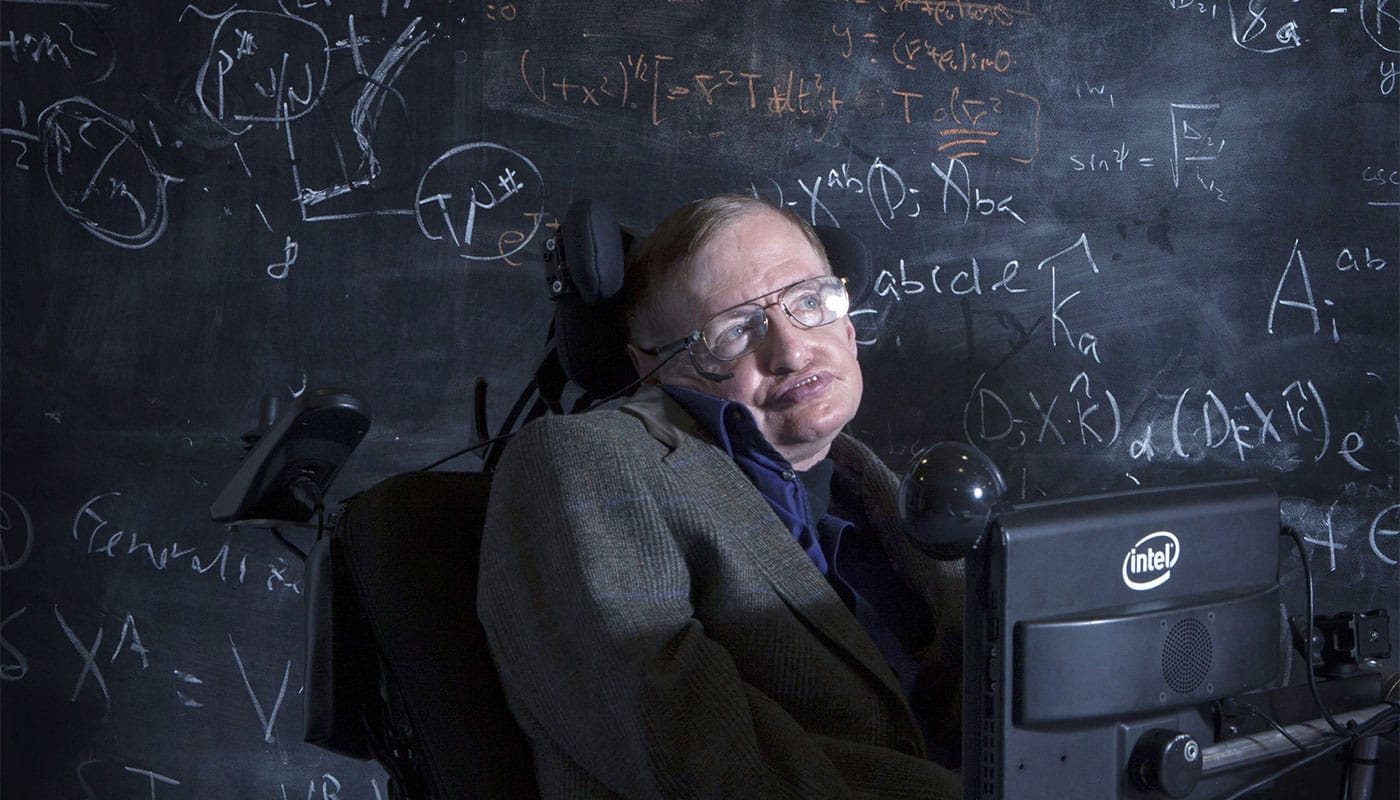

Before I came to be disabled, I had always known Stephen Hawking as a genius. A scientist to whom I could not compare. He was more impressive than me in every way, and he had a disability. So what? My able-bodied self was impressed with his accomplishments and looked to him with great respect.

That acknowledgement of his mind’s great potential would prove to be important lesson to me years later.

In 2013, less than a year after my car accident, I was struggling with hopelessness. My countless surgeries were not yielding positive results, and I truly felt as though I would spend the rest of my life in bed. As someone who had lived with a definitely able body for 23 years, my mind naturally resisted the concept of moving on with a limited physical capacity.

A text message from one of my friends in July 2013 shifted my path.

Stephen Hawking. He has more physical limitations than you will ever have but the world knows who he is.

It was an attempt to lift me out of despair and force me to realistically consider the challenges ahead. My injuries were non-fatal, non-terminal and there was plenty of hope for recovery, even if I would rely on a wheelchair for my mobility. Stephen Hawking’s mind had managed to do more with less on the physical side, and that really focused me.

How had Stephen managed to achieve so much? The answer surprised me: He succeeded because he chose to. He focused his mind and carried out the mental labors required to produce a body of work and discovery that have made him a legend.

The following statement, which has made its way around the web in memes, was something I discovered while laying in a hospital bed, fresh off my first amputation.

My advice to other disabled people would be, concentrate on things your disability doesn’t prevent you doing well, and don’t regret the things it interferes with. Don’t be disabled in spirit, as well as physically.

In other words, don’t dwell on what has been lost and move forward. Hearing that from Stephen himself, albeit through a New York Times interview, made the message so much more credible than hearing it from friends or family members who had no concept of my internal struggle.

In that same interview, Stephen said something that I thought to be a lie.

I don’t have much positive to say about motor neuron disease. But it taught me not to pity myself, because others were worse off and to get on with what I still could do. I’m happier now than before I developed the condition.

I phrase it a little differently, but the basic idea is the same. I wouldn’t trade my life today (physical limitations and all) with the one I had before my car accident. My past life was great. But my experiences with disability have allowed me to gain so much in understanding, knowledge, compassion and love—things I would never be willing to trade for walking.

Stephen Hawking was a hero to me. His example pulled me from the depths of despair and encouraged me to seek out new possibilities. My story of his impact is surely not unique, and I suspect it will remain a part of his legacy for many years to come.

May his memory empower others to overcome the challenges of disability, and may he rest in peace.