American Airlines recently instituted a new policy that prohibits power wheelchairs weighing more than 300 pounds (and in some cases 400 pounds) from flying on its American Eagle regional jets. The policy has not been published online and the carrier has refused multiple requests to explain its justification for the change, which has not been adopted by other carriers.

My home airport of Gainesville, Florida is one of the 130 airports in the United States where American uses only regional jets. Despite the fact that the arbitrarily imposed weight restriction appears to be an egregious violation of the Air Carrier Access Act, American refused to budge from its position. If I was going to fly, I had no choice but to reduce the weight of my wheelchair by whatever means necessary.

The “Chop Shop” approach

I took my wheelchair to be assessed by a licensed repair technician and asked them to act the part of a “chop shop” for the day — removing parts that I could potentially do without for a single trip.

We removed a number of pieces, including the articulating leg rest, which was prescribed by my doctor as a tool to prevent further contraction of the muscles in my residual limbs. For those who don’t know, amputees who do not use prosthetic devices are at significant risk of contracture, which limits one’s already severely challenged mobility. The muscles in my right arm have contracted, making it impossible to straighten the arm — it is permanently “locked” in a bent (contracted) position. I certainly don’t want that to happen to my legs!

The foot plates were also removed, an action that was only possible because I no longer have feet. Most power wheelchair users affected by American’s ban still have their feet.

Battery Removal

Even after removing the hydraulic leg rests, foot rests and a number of other minor pieces, the wheelchair still weighed well over 300 pounds. The only thing left to remove were the batteries, which typically weigh between 40 and 50 pounds apiece.

For more than a decade, the majority of power wheelchairs have come standard with gel or “dry cell” batteries, specially sealed to ensure that battery acid cannot leak, making them safe for transport. Because the batteries are enclosed securely within the chair’s housing, the DOT and FAA have instructed airlines to leave gel batteries alone. According to 382.127(c), “If the battery on the passenger’s wheelchair or other similar mobility device has been labeled by the manufacturer as non-spillable…you must not require the battery to be removed and separately packaged.”

The technicians at my wheelchair repair shop strongly advised against removing the batteries, suggesting that damage would be likely to occur if the chair was disassembled and reassembled by untrained personnel. They were right, but I’ll come back to that later.

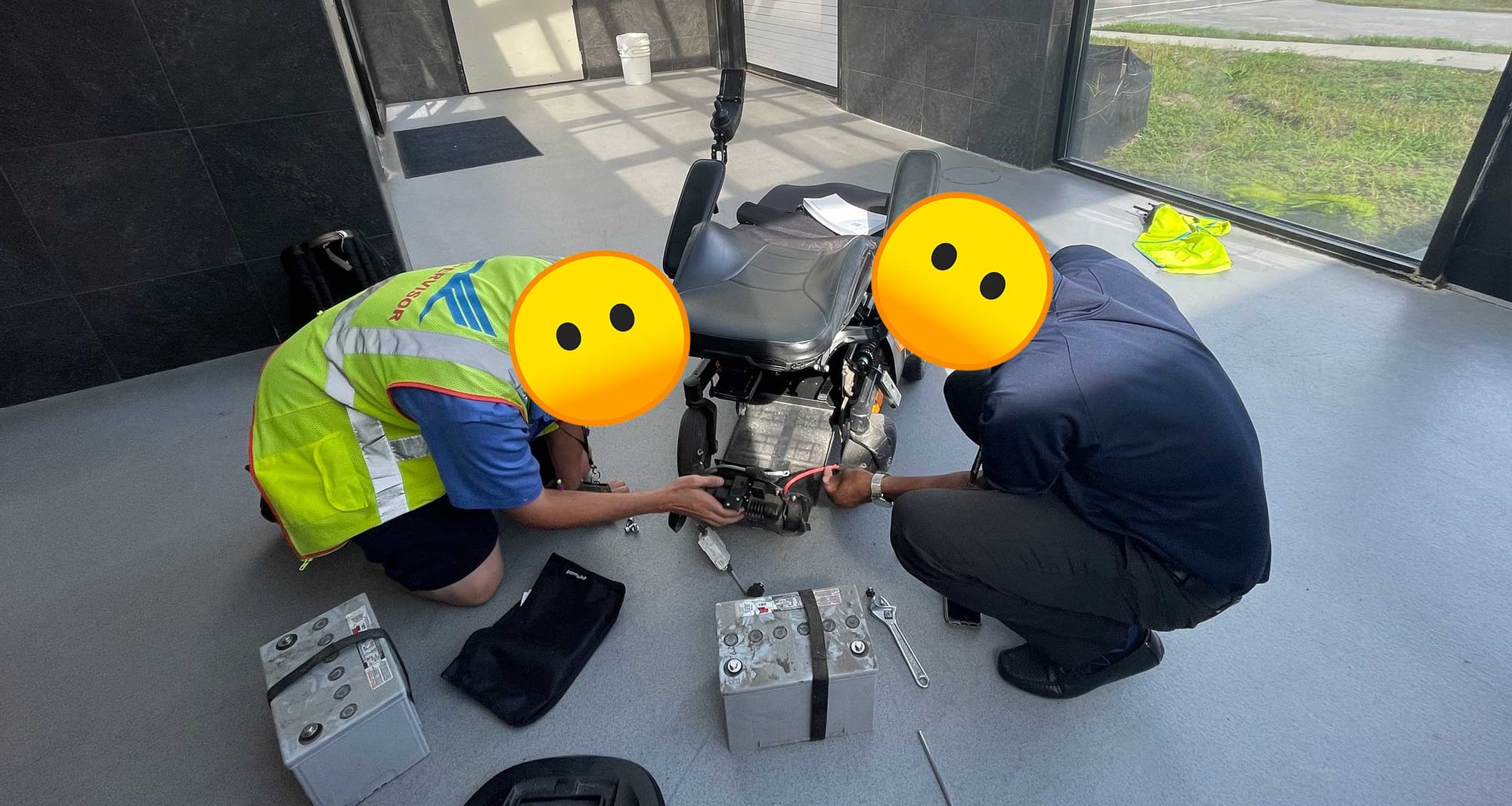

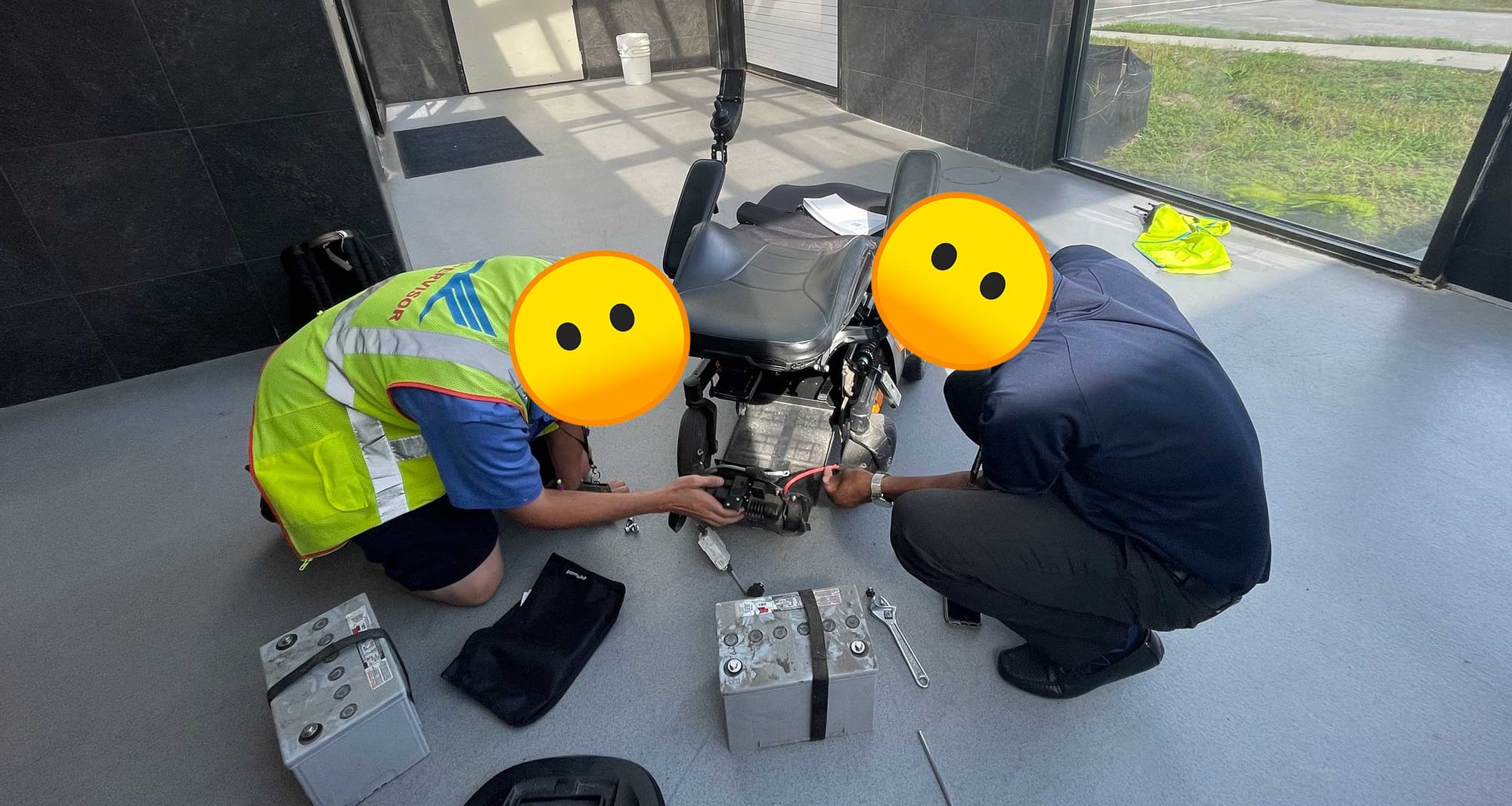

When I arrived at the Gainesville Airport last Wednesday, the staff had been informed that the batteries would have to be removed. I handed them the manual that came with my wheelchair, along with a few wrenches provided by the manufacturer. That completed my obligation under §382.129 to “provide written directions concerning the disassembly and reassembly” of my power wheelchair, but the staff still asked me to watch them take apart the chair while seated in an uncomfortable and unpadded airport wheelchair.

It was good that I was there, because they forgot to flip the power breaker switch before taking the chair apart. This was step one in the manual, and I asked them to “double check” that they had done so just as they began working with the battery directly. In addition to the written instructions that I provided, the Gainesville team also consulted YouTube. The disassembly took 45 minutes but went surprisingly well — a stroke of good luck — and the batteries were packaged in battery boxes for transport.

Following this lengthy process, I had to be pushed through the terminal, to the gate and down the jet bridge in an airport wheelchair, which frustrated me. My wheelchair had been disassembled in the terminal, which meant that I could not turn it over at the aircraft door as I have always done before.

Your support makes this website and my continued accessible travel advocacy possible. Please consider joining the movement to make travel accessible for everyone by upgrading to a paid subscription today.

Dramatic reassembly at Charlotte Airport

Upon arrival to Charlotte Airport, I informed the staff that my wheelchair would need to be reassembled as per §382.129(b) which states that “when wheelchairs, other mobility aids, or other assistive devices are disassembled by the carrier for stowage, you must reassemble them and ensure their prompt return to the passenger.”

Multiple agents boarded the flight and told me that they couldn’t reassemble the chair because they weren’t trained and that I would need to do it. “I’m a triple amputee with only one hand, so no — I won’t be able to put the wheelchair back together.” I provided the instructions in the manual and suggested that they refer to YouTube for a visual aid just as the Gainesville team had done earlier.

The assistance staff had initially asked if I wished to wait onboard, in the jet bridge on an aisle chair, or in an airport wheelchair. I chose to remain onboard in the padded airplane seat, as I always do when waiting for the return of my wheelchair. But shortly thereafter, one of the pilots and an airline representative told me that I was required to get off, presumably so the aircraft could be on its way to its next destination. I refused, and was told they would call the police to remove me if necessary. The pilot asked, “Do you really want to go down this route?” I remained onboard despite the pilot’s threatening behavior. The police were never called and an American Airlines manager later apologized to me for the pilot’s unacceptable behavior.

The Charlotte team eventually got to work and the chair was put back together (for the most part) in about 50 minutes. I immediately noticed that a piece of the plastic shroud had been cracked, but the chair turned on and moved, which was far better a result than I expected.

After being reunited with my wheelchair (finally), I proceeded to my next flight from Charlotte to Las Vegas, which was operated by a Boeing 737 (with the same cargo door clearance height as the regional jet). The batteries were permitted to remain intact and the flight was generally uneventful.

The real damage done to my wheelchair appeared later and it’s a big problem

When I arrived to my Las Vegas hotel, my power wheelchair’s battery indicator began flashing with a single red bar, despite the fact that I had used at most 25% of its battery capacity that day. Over these last days, this has continued to be a problem — leading me to believe that the batteries were either not properly reconnected or were damaged during transport.

Because I have been unable to trust the power beneath me, I’ve had to use taxis much more frequently, even for short journeys that I would have traditionally made on my own. I’m concerned every time I go out, having no idea what the chair’s capacity might actually be. One minute, the battery indicator shows a full charge, the next minute it’s flashing a warning that the battery is dangerously low. It’s as dysfunctional as American Airlines.

A civil rights disaster

Due to a new arbitrary, unnecessary and discriminatory policy, American Airlines forced me to remove critical, medically necessary pieces of my wheelchair in order to take a flight that I had taken many times previously with a fully intact wheelchair that then weighed some 450 pounds.

In the course of my trip, I allege that American Airlines violated the following Air Carrier Access Act regulations:

- §382.125(a/b) and §382.125(a), which prohibit airlines from refusing to carry power wheelchairs as they did to me on October 21, 2018.

- §382.125(c), which requires airlines to provide for the use of personal wheelchairs all the way to the aircraft door.

- §382.127(c), which prohibits airlines from requiring that non-spillable batteries be removed from power wheelchairs.

- §382.129(b), which requires that airlines reassemble wheelchairs and promptly return them in the same condition in which they were received.

There were other violations of federal regulations, too, such as the failure of flight attendants to provide an individualized safety briefing to disabled passengers as required by §121.571.

For most power wheelchair users, particularly those who still have their legs or who have even more specialized equipment than I do, air travel to up to 130 U.S. airports may still be impossible on American Airlines.

Next week, I will be providing an update on my advocacy efforts, which will include an opportunity for you to become involved in this fight for equal access in air travel. Thank you for your continued support!