Last week, I needed to fly from Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C. to JFK Airport in New York City. Only two carriers offer nonstop service between those airports, and American Airlines (my carrier of choice) was not among them. That left Delta and JetBlue, the latter of which I had never flown before. Due to my past experiences with disability discrimination at Delta, booking the trip with JetBlue was an easy decision.

JetBlue Airways Corporation was founded in 1998, and began flying on February of 2000. The airline’s headquarters are in New York City, and its primary hub is at JFK Airport. A fleet of 228 aircraft carry passengers to more than 100 destinations in the United States, Mexico, Central America, South America and the Caribbean. In the U.S., the route map connects major cities in 29 states including Alaska. While it isn’t a truly global carrier, JetBlue does compete with American, Delta and United on many domestic routes. It has grown to become the 6th largest airline in the United States.

Having heard many of my friends speak highly of the carrier, I was eager for my first flight. The competitive one-way fare of around $50 didn’t hurt either.

Unfortunately, on the day of the flight, I experienced a myriad of issues that left me with a less than favorable opinion of JetBlue. The inbound aircraft was delayed, causing us to miss our departure slot and be subjected to a hold of about 40 minutes. Still, delays happen and I was willing to give JetBlue a pass.

On arrival to JFK, though, I watched as my wheelchair was the last item removed from the cargo hold. It was left to sit on the belt loader for more than 20 minutes, delaying its return to me until long after the other passengers had deplaned. The delayed return of my wheelchair, compounded with our delayed arrival, caused me to miss the last viable public transit connection to my hotel in New Jersey. Not wanting to pay an exorbitant cab fare, I made alternative arrangements for accommodation closer to JFK. My hotel in New Jersey, a Hyatt Regency, graciously allowed me to cancel without penalty.

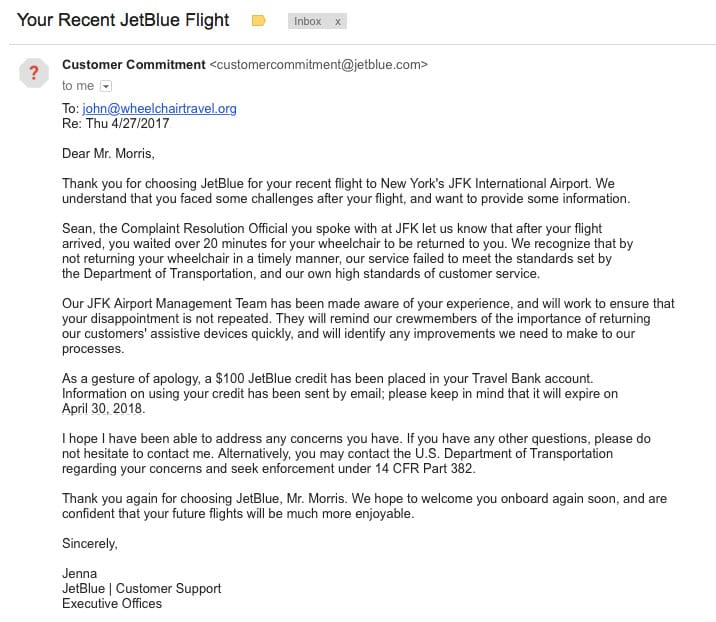

A few days after my flight, I received a surprise e-mail from a customer support representative at JetBlue’s Executive Office. A screenshot of the message is pasted below:

The e-mail was unsolicited, as I had not sent a complaint to the airline or to the Department of Transportation. Although the e-mail references that I had spoken with a CRO at the airport, I was not aware that the manager providing updates on my wheelchair’s status was a CRO. I had not filed a report, nor had I asked for a response from the airline.

JetBlue’s e-mail was a response – not to me – but to an issue. The airport agent discovered a failure in service affecting me and escalated the matter to the airline’s corporate office. The result of that escalation was this e-mail, in which the carrier not only apologized, but admitted a violation of the Air Carrier Access Act. I’m impressed by that, because getting an admission of guilt out of American Airlines is like pulling teeth, even in far more egregious scenarios.

As a gesture of goodwill, JetBlue sent me a $100 voucher good towards future travel. That’s not a big sum, but the impact it had on my opinion of the carrier was substantial.

Upset by my experience, I had vowed to pass on future travel with JetBlue. The surprise e-mail impressed me, though, because it showed that the airport agents had taken it upon themselves to speak up for me. The involvement of the executive office, its attention to the service failure and the sincere attempt to gain back my trust was well received. A simple e-mail can go a long way – it did, and I look forward to my next trip with JetBlue.

What do you expect from an airline after a service failure?

Has an airline ever been proactive in their service recovery?