Prior to my car accident, I wrongly assumed that disability is rare — the disability community, I thought, comprised only a small percentage of the world’s population. Like most nondisabled people, I was ignorant of the reality and in need of education. Thankfully, through my own disability and advocacy journey, I’ve wised up and am able to speak about the disabled travel experience using data to support my arguments.

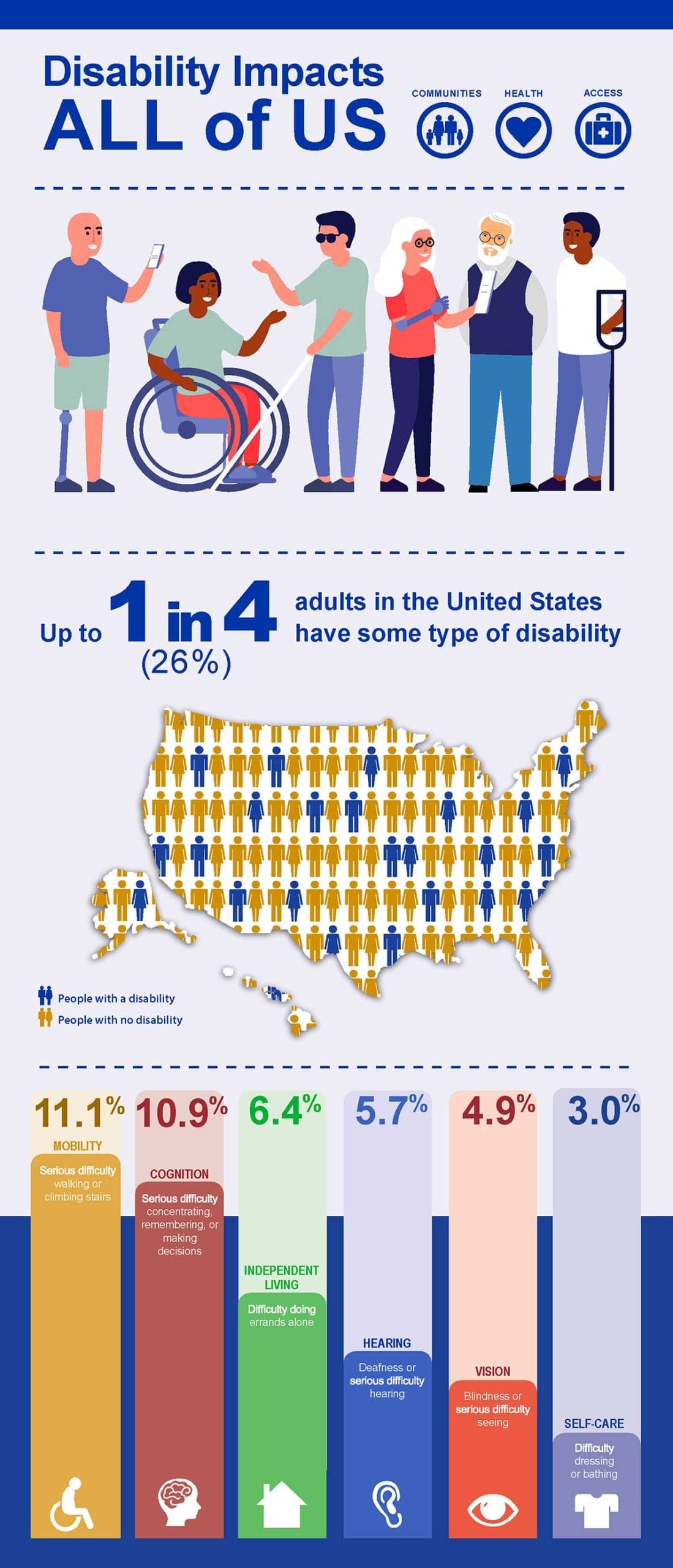

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that up to 26% of American adults have one or more forms of disability — each of whom possesses a right to equal access in the United States. The following infographic digs a bit deeper into this statistic:

Were disabled people equitably engaged and represented in our society, 1 in 4 people we meet would have a disability — that’s 1 in 4 people in shopping malls, restaurants, sports stadiums, movie theaters, airports, hotels, etc. As the CDC identifies 11.1% of adults as having “serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs.” we can expect a large number of those people to use a wheelchair or mobility device at least some of the time — including (or perhaps especially) when traveling by air.

Airline Industry Insider Resurfaces the “Jetway Jesus” Lie

I recently stumbled upon an article in The Hill, written by airline industry insider Jay Ratliff who, according to his profile, “spent over 20 years in management with Northwest/Republic Airlines, including as aviation general manager.” The article’s headline referred to disabled travelers as a “four-wheeled problem” for airlines that is “only going to get worse.”

According to Ratliff, the large number of wheelchair assistance requests on flights between popular retirement and vacation destinations is evidence not of a large and vibrant disability community, but rather a conspiracy to gain priority service free of charge. “Obviously,” he writes, “many passengers are simply trying to take advantage of the preferential treatment that people in wheelchairs receive to board early.” To back up his claim, Ratliff references the following TikTok video:

The young vacationer who created the video was surely seeking social media attention, much like the influencer who allegedly faked an injury to score a business class upgrade in 2020 (it was most likely staged). After watching the video and comparing this passenger to the amputees, paraplegics, blind and elderly passengers who have boarded early with me on my nearly 1,000 flights as a wheelchair user, I don’t see a resemblance.

Nevertheless, Ratliff and others continue to espouse the “Jetway Jesus” myth, which suggests passengers who use wheelchair assistance at departure but make their own way on arrival are faking disabilities.

The proposed solution to a nonexistent problem? Make disabled people board last!

Like most airline managers, Ratliff blames the inefficiency of airline operations on the presence of disabled passengers rather than airline schedules with impossibly tight turnaround times, decisions to squeeze more passengers into smaller seats, checked baggage fees that force passengers to stuff their wardrobe into a carry-on, and poorly designed airport terminals. No, Ratliff says nothing of those issues, but he does say this:

Airlines are still short staffed in many areas, and having such a presence of passengers needing assistance at the gate puts many flights in jeopardy of departing late. Late flights mean reduced operating profit, but there is only so much that can be done to fix the problem.

The fix, he says, is to force disabled passengers to board last:

The easiest way to immediately fix the problem is to have those requiring more time to board go last. Yes, after everyone else has boarded. This would remove the temptation for those who are faking an injury and would mean far fewer wheelchair requests.

It’s a ridiculous notion, but let’s give it a try! Over my next 10 flights, I will commit to surrendering my civil right to preboard the aircraft (airlines rarely respect it anyway). As part of this commitment, I will refuse to cross the gate threshold until the very end of boarding, which is generally 15 minutes prior to scheduled departure. If my flights take a delay, the impacted gate agents, flight crews and passengers can place the blame on Mr. Ratliff’s discriminatory strategy for solving the airline industry’s “four-wheeled problem.”